In 1999 I wrote a paper for the journal Health and Social Care in the Community titled Joint working in community mental health: prospects and challenges. The back story is that the work for this article was mostly done during my first year of part-time study for an MA in Health and Social Policy, during my time working as a community mental health nurse in East London.

In 1999 I wrote a paper for the journal Health and Social Care in the Community titled Joint working in community mental health: prospects and challenges. The back story is that the work for this article was mostly done during my first year of part-time study for an MA in Health and Social Policy, during my time working as a community mental health nurse in East London.

Frustratingly, I can’t find my original wordprocessed copy of this paper from which to create a green open access version for uploading to the Orca repository and for embedding a link to here. But not to worry. The abstract, at least, is a freebie:

This paper reviews the opportunities for, and the challenges facing, joint working in the provision of community mental health care. At a strategic level the organization of contemporary mental health services is marked by fragmentation, competing priorities, arbitrary divisions of responsibility, inconsistent policy, unpooled resources and unshared boundaries. At the level of localities and teams, these barriers to effective and efficient joint working reverberate within multi-disciplinary and multi-agency community mental health teams (CMHTs). To meet this challenge, CMHT operational policies need to include multiagency agreement on: professional roles and responsibilities; target client groups; eligibility criteria for access to services; client pathways to and from care; unified systems of case management; documentation and use of information technology; and management and accountability arrangements. At the level of practitioners, community mental health care is provided by professional groups who may have limited mutual understanding of differing values, education, roles and responsibilities. The prospect of overcoming these barriers in multidisciplinary CMHTs is afforded by increased opportunities for interprofessional ‘seepage’ and a sharing of complementary perspectives, and for joint education and training. This review suggests that policy-driven solutions to the challenges facing integrated community mental health care may be needed and concludes with an overview of the prospects for change contained in the previous UK government’s Green Paper, ‘Developing Partnerships in Mental Health’.

Fifteen years on the structural divisions remain. As with other areas, community mental health care continues to be funded and provided by a multiplicity of agencies, with ‘health care’ and ‘social care’ distinctions still very much in place. This year’s Report of the Independent Commission on Whole Person Care for the Labour Party and the King’s Fund’s work on integrated care are examples of recent initiatives aimed at closing these gaps. Labour’s Independent Commission recommends the creation of a new national body, Care England, bringing together NHS and local authority representatives at the highest level. Note, of course, that these proposals are for England only: these are ideas for health and social care in one part of a devolved UK.

In my article I drew attention to the problem of competing policies and priorities for NHS and local authority organisations, the lack of shared organisational boundaries, non-integrated information technology systems and separate pathways bringing service users into, through and out of the system. An illustrative example I gave was the parallel introduction, in the early 1990s, of the care programme approach (CPA) and care management. Here in Wales, with the introduction of the Mental Health (Wales) Measure there is now, at least, a single care and treatment plan (CTP) to be used with all people using secondary mental health services. But how many health and social care organisations in Wales and beyond have managed to integrate their information systems? This, I suspect, remains an idea for the future.

And then there are the distinctions, and the relationships, between the various occupational groups involved in community mental health care. In my Joint working paper I emphasised the differences in values, education and practice between (for example) nurses and social workers, and (perhaps rather glibly) suggested that the route to better interprofessional practice lay through clearer operational policies at team level. Getting mental health professionals to work differently together became, for a time at least, something of a policymakers’ priority in the years following my article’s appearance. Here I’m thinking of the idea of distributed responsibility, and ‘new ways of working’ more generally, of which more can be found in this post and in this analysis of recent mental health policy trends (for green open access papers associated with both these earlier posts, follow this link and this link).

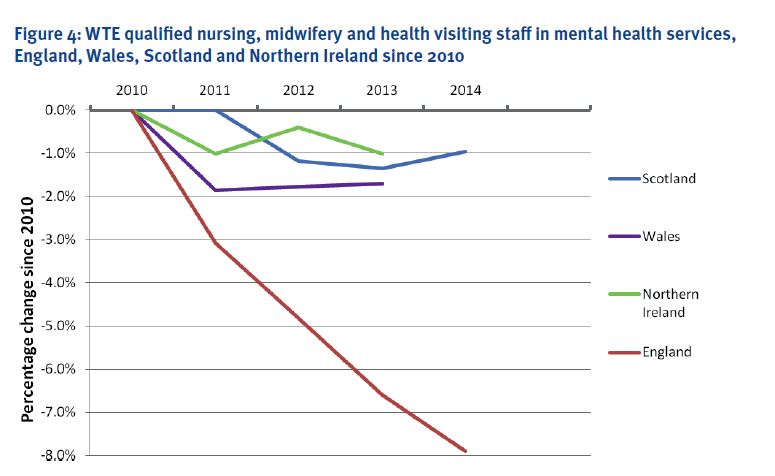

Two other things strike me when I look back on this 1999 article and reflect on events in the time elapsing. First is how much I underemphasised, then, the importance and influence of the service user movement. Over 15 years much looks to have been gained on this front, and I detect improved opportunities now for people using services to be involved in decisions about their care. Services have oriented to the idea of promoting recovery, as opposed to responding solely to people’s difficulties and deficits. This all takes me neatly to COCAPP and Plan4Recovery, two current studies in which I am involved which are investigating these very things in everyday practice. Second, I realise how little I foresaw in the late 1990s the changes then about to happen in the organisation of community mental health teams. Not long after my paper appeared crisis resolution, early intervention, assertive outreach and primary care mental health teams sprung into being across large parts of the country. More recent evidence suggests a rolling back of some of these developments in a new era of austerity.

And what of the community mental health system’s opportunities and challenges for the fifteen years which lie ahead? Perhaps there’s space here for an informed, speculative, paper picking up on some of the threads identified in my Joint working piece and in this revisiting blog. But that’s for another day.

Here’s a post to draw attention to the

Here’s a post to draw attention to the

I’m just back from Horatio’s latest gathering: the

I’m just back from Horatio’s latest gathering: the

In 1999 I wrote a paper for the journal Health and Social Care in the Community titled

In 1999 I wrote a paper for the journal Health and Social Care in the Community titled