I take the view that ‘everything is connected to everything else’, to use a phrase I recently learn is attributed to Leonardo da Vinci. More on him later.

Over the past week I’ve been involved in industrial action as part of #UCUStrikesBack. What I’m not going to do in this post is to explain why university staff are currently on strike, largely because this has already been adequately covered elsewhere (for example, see here and here). Instead, I want to share some picket-line reflections linking what happens in universities with what happens in the health service. These are connections which are not being made frequently enough, including by some who should know better.

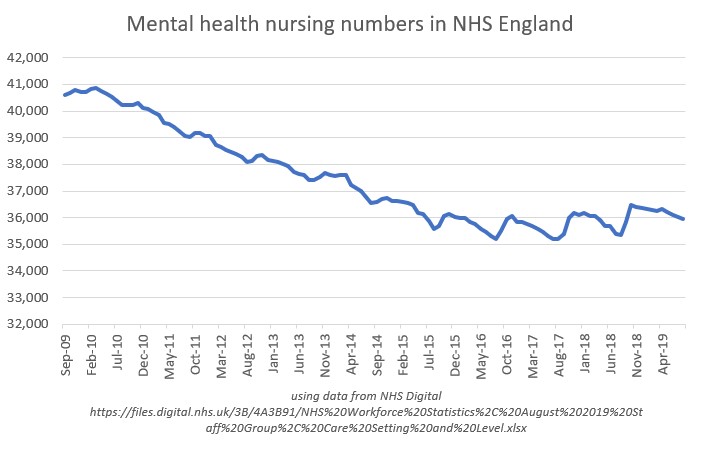

As a mental health nurse academic I am acutely aware of the perilous position occupied by my profession in the NHS, with reports from earlier in 2019 pointing to a loss of 6,000 mental health nurses in NHS England since 2009. Below is a graph, created using NHS Digital data, which starkly reveals the current situation:

As an aside, data of this type are not published here in Wales. They should be. In any event, quite correctly much concern has been expressed about this startling decline in the workforce, with mental health nursing now singled out as a group needing particular help to improve both recruitment and retention.

As an aside, data of this type are not published here in Wales. They should be. In any event, quite correctly much concern has been expressed about this startling decline in the workforce, with mental health nursing now singled out as a group needing particular help to improve both recruitment and retention.

Reflecting my position as a health professional academic I hold joint membership of the University and College Union (UCU) and the Royal College of Nursing (RCN). The RCN, along with other health service unions like Unite and Unison, is trying to reverse the crisis facing the nursing workforce. It is campaigning on safe staffing, has published a manifesto to assist nurses wanting to interrogate prospective parliamentary candidates ahead of the December 2019 general election, and through its Fund our Future campaign is lobbying government to reverse the removal of tuition fee and living cost support for students of nursing in England.

These campaigns are important. So far, however, in its public pronouncements the RCN has failed to make the necessary connections between working conditions in universities and the present and future education of student nurses. Put simply, an adequate supply of educated, evidence-minded, person-centred nurses demands an adequate supply of secure, well-supported, fairly paid nurse educators and researchers. Nurse academics typically have career trajectories which are significantly different from those in other fields, with implications for their recruitment, retention and development. The modern norm for historians, physicists and sociologists seems to involve years of precarious, post-doctoral, employment characterised by repeated short-term contracts before landing (if ever) much sought-after full-time academic posts. In contrast, with some exceptions nurses are generally recruited into higher education by dint of their practitioner expertise, their posts linked to the servicing of courses of professional study. This was certainly how it was for me: my academic career commenced with an initial series of short-term employment contracts associated with the leading of a post-qualification course for community mental health nurses. In all universities, nurse academics can soon find themselves carrying major teaching and course management responsibilities, often for programmes and modules of study which run more than once across a single year. Demanding education and education-related workloads can squeeze out time for research, scholarship and wider engagement, in workplaces which traditionally value productivity in these areas for the purposes of career progression.

Expanding the number of nurses to fill the gaps which now exist, for which the RCN and others are rightly campaigning, requires thought and careful planning. In the run-up to the general election both are in short supply as nursing numbers become reduced to political soundbites. More student nurses must mean more nurse academics, but in any future rounds of staff recruitment potential entrants will have their eyes wide open. The erosion of university pensions relative to pensions in the NHS does nothing to encourage those contemplating the leap from health care into higher education (or, at least, into that part of the sector in which the Universities Superannuation Scheme predominates). Very reasonably, those considering future careers as nurse academics will also want to weigh up the appeal of doing work which is undoubtedly creative and rewarding with what they will hear about workloads, developmental opportunities and work/life balance.

I also learn, this week, that Leonardo da Vinci saw the making of connections as necessary in order that we might see the world as it truly is. In my working world, education, research and practice are intimately intertwined. It is disappointing that these connections are being missed by organisations which campaign on the state of nursing and the NHS, but which do not (as a minimum) also openly acknowledge the concerns that nursing and other academics have regarding the state of universities. Right now, some words of solidarity and support would not go amiss.

Follow @benhannigan Over on the website of

Over on the website of  Earlier this month I joined colleagues at the main meeting of the

Earlier this month I joined colleagues at the main meeting of the  Big thanks to the Board of Directors of the

Big thanks to the Board of Directors of the

Mental health nursing is important and fulfilling work, and offers a fine and rewarding career. More people also need to be doing it. By way of background, last month Mental Health Nurse Academics UK (MHNAUK) submitted

Mental health nursing is important and fulfilling work, and offers a fine and rewarding career. More people also need to be doing it. By way of background, last month Mental Health Nurse Academics UK (MHNAUK) submitted

Happy new year. In December 2017, I was pleased to see

Happy new year. In December 2017, I was pleased to see  In previous posts (see

In previous posts (see  October has been a month of external events. These began with the inaugural All Wales Mental Health Nursing and the

October has been a month of external events. These began with the inaugural All Wales Mental Health Nursing and the